A medical team in London, Ont., has achieved a Canadian first: a groundbreaking technique that boosts the viability of donor organs.

This breakthrough offers new hope for transplant patients by significantly increasing the pool of available organs, potentially saving countless lives.

The technique, called abdominal normothermic regional perfusion (A-NRP), works by pumping blood to abdominal organs after circulatory death (when the heart stops beating). This allows organs to be re-oxygenated and warmed to normal body temperature — minimizing damage and enhancing their chances of survival after transplantation.

The team at Lawson Health Research Institute, led by Dr. Anton Skaro, is pioneering the use of A-NRP in Canada. They believe this technique has the potential to increase organ transplants in Canada.

“The biggest challenge that transplant physicians and surgeons face is organ shortage. There are just not enough organs to go around. And patients die every year on the wait-list in the hundreds to thousands range in Canada,” said Skaro, director of livery transplant surgery at the London Health Sciences Centre.

“There are many donors and donor families with wonderful intentions to donate this beautiful gift of life. Unfortunately, through the dying process, many of those organs are just too damaged to be safely transplanted.”

In 2023, more than 3,400 organ transplants were performed in Canada; 83 per cent of transplants used deceased donor organs and 17 per cent used living donor organs, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Of the 952 deceased donors in 2023, 67 per cent donated following neurological determination of death, often known as brain death, and 27 per cent donated following death determination by circulatory criteria, often known as cardiac death.

Circulatory death and organ donation

Organ donation after circulatory death is historically been less reliable compared with brain death donations, Skaro said. This is because there is a higher risk of organ damage after circulatory death since oxygen and blood flow stop.

Once a patient’s heart stops beating, blood pressure drops and the circulation of oxygen and nutrients to the organs is compromised. This leads to a condition called warm ischemia, which irreparably damages the metabolic machinery of the organs, Skaro explained.

“Unfortunately, through the dying process, the organs are very seriously damaged and many of them are not rendered suitable for transplantation … and that’s a heartbreaking situation,” he said.

However, the use of A-NRP has the potential to protect organs after circulatory death and could significantly increase the likelihood of successful transplants.

How it works

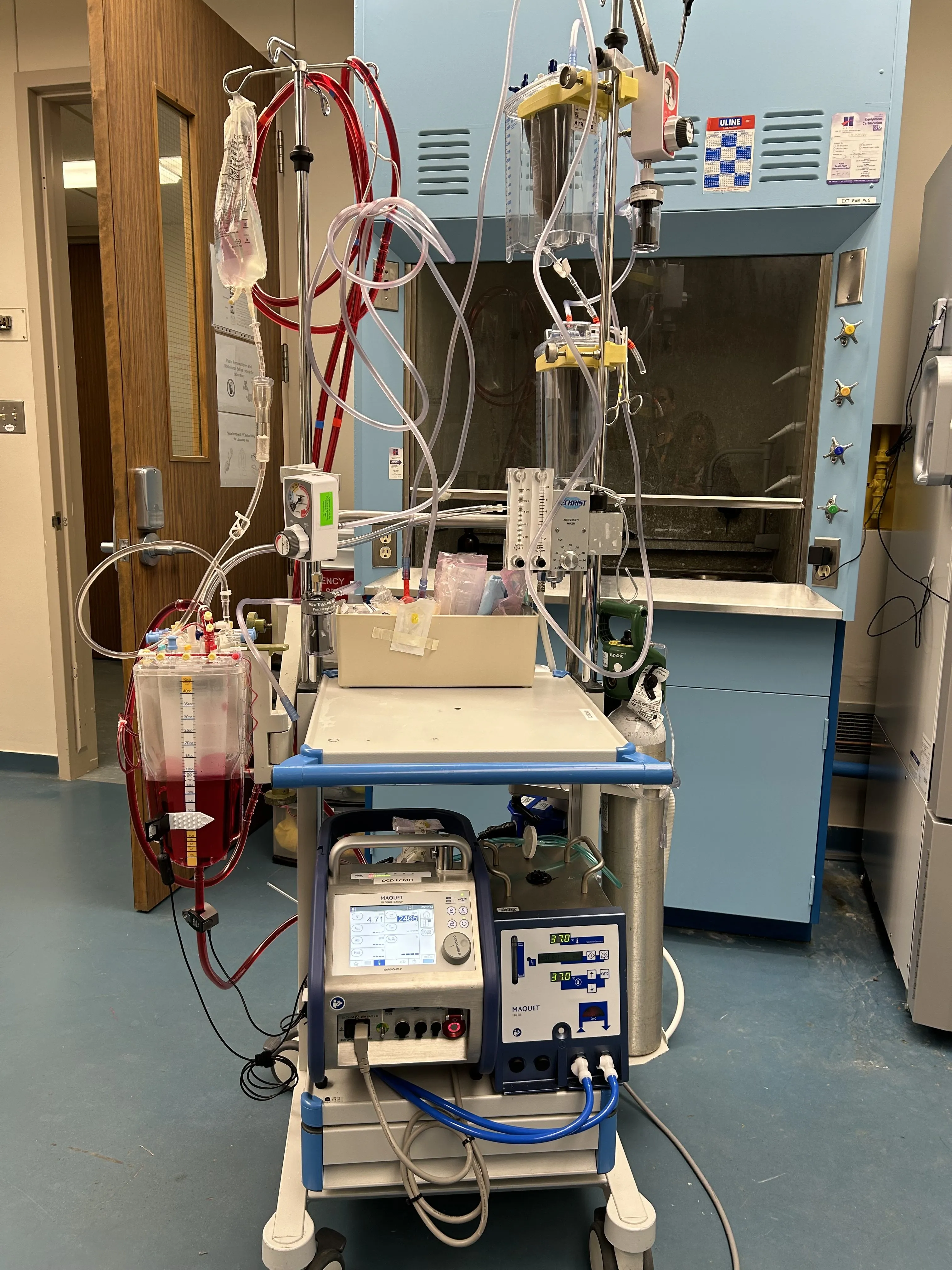

A-NRP works by using a specialized pump to restore blood flow to the abdominal organs of a donor after circulatory death, Skaro explained.

“After death declaration, there’s a mandatory five-minute period of time that we call a hands-off period. And that’s to reduce the likelihood that the patient can auto-resuscitate spontaneously,” he said.

“Once that’s done, the patient is brought to the operating room. And at that point, we exclude the abdomen from the rest of the body and then insert cannulas (flexible tubes) into the artery and vein and then start circulating blood to the abdominal organs.”

This allows the organs to receive a fresh supply of oxygen and blood, aiding in their recovery after the damage incurred during the dying process.

“We’re able to get rid of many of the toxic agents that are circulating within the organs that compromise their function,” Skaro said. “And so, essentially, what we’re doing is preconditioning that organ, so that it’s able to replenish its energy, replenish its molecules that are capable of counteracting this injury. And so they behave and perform far better during the transplantation.”

He said using this method is a great opportunity to not only “vastly increase the organ supply” but also provide better quality organs.

While the procedure is a first in Canada, it has been used in other nations, including in Europe, he explained.

The technology required for this has been available for a long time in Canada — Skaro described it as a portable heart and lung machine typically used to transport patients who have experienced cardiac arrest. However, his team has adapted this pump and integrated it into the organ donation process as well.

“We’re using these amazing techniques, thinking outside the box to try and solve our organ shortage problem,” he said.

First in Canada

On April 10, the medical team at the London Health Sciences Centre successfully implemented A-NRP for the first time in Canada. This procedure optimized organs from two donors, allowing for the transplantation of two kidneys and two livers to four patients.

“The liver is here in London, as well as one kidney. And we actually were able to send one of the kidneys to Hamilton. And our colleagues in Hamilton were able to transplant that kidney successfully as well,” Skaro said.

“This is a huge team effort that we’re looking to scale, not just throughout the province, but eventually nationally to all jurisdictions in the country, hoping that we can do everything in our power to increase the number of available organs and stop anyone from dying on the wait-list without one.”

Currently, the technique has been limited to abdominal organs. The next step is to scale up this method to include thoracic organs, such as the heart and lungs.

“We have interested parties both on the side of the heart transplant and the lung transplant realms. And this is going to potentially move into their domain where heart transplants will be feasible from these kinds of donors, which is astounding,” Skaro said.

— with files from Global News’ Katherine Ward